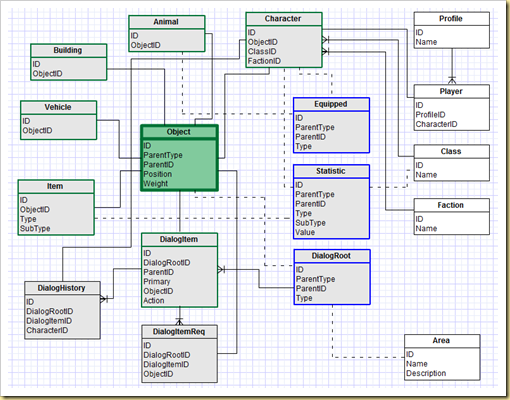

(2012) This post was written long before I had much game development experience. It’s more of a concept design, rather than actual reality. So really I was blowing a little smoke :)

Answer: Pretty much anything.

Like business applications, every RPG Game (Focusing on that particular genre) will have a different Database. Design, Technology, Feedback .. They all affect a Database.

This Database is simple, and quite incomplete.

Remember, the goal of this series is not to create a fully realised RPG Database. It’s to show how Clarion can be used in creating a Backend Administration app for said database.

Design Decisions (Random Intro Points):

- A Class system for Players (and other Characters) would be implemented. One Class for one Character.

- A Character can be Player or Non-Player.

- The Object table is pretty much the center of this Database.

- Character, Animal, Building, Vehicle and Item are all “Children” tables to the Object.

- DialogItem is also a child table, but it’s special. Get to that later.

Let’s start breaking up this puppy.

Object

| Object | |

| ID | |

| ParentType | “Area”, “Character”, .. |

| ParentID | |

| Position | Context on ParentType |

| Weight |

As mentioned, it’s the center. The sun. Around which the rest of the Game revolves.

The Object contains physical characteristics, models, meshes (in Child tables, not in the db above). Most of these integrate with the technical aspects of the Engine. I decided it was outside the scope of this discussion. Oh, also, I wasn’t smart enough to figure it out.

Of major importance is that an Object represents the physical instance of the Entity.

Of course, not all Objects are going to be in the Database. Some of them, probably a lot depending on game design, will be generated in-game.

The ParentType field links to what “Parent” it is under. Which is either the Character (Bags, Items in Character Slots) or Area.

Let’s take a look at the Area.

Area

| Area | |

| ID | |

| Name | |

| Description |

Imagine your favourite RPG. When you start the game, you start somewhere. This is, in our particular game, the Area. It’s a village; surrounding countryside; cave with evil goblins; cave with misunderstood goblins.

At the moment, it’s just that. A record that is parent to a bunch of Objects. Of course, you’d need size measurements for the Area. You’d need to know boundaries.

This game could have a big persistent world, full of many Areas, or Nodes. That’s up to the Engine.

Profile (Not Used)

| Profile | |

| ID | |

| Name |

The Profile table allows the Engine to know that you are “Stu Andrews” and that you have four “Player” Character records (attached to the Profile record).

A Barbarian Scholar, a Guitar Bard, and two Monkey Ninjas. They are all at different Levels, and they are all at different stages within the Game.

Obviously we don’t have the Profile table in the Backend Database. Unless we were going to have a default Profile record, which we’re not.

Player (Not Used)

| Player | |

| ID | |

| ProfileID | |

| CharacterID |

Quite an important table. I guess if you don’t have this one, the game is just a simulation.

The ProfileID field is what links the Player records to your Profile record in the Game.

Via the CharacterID field, this table tells the Engine which Character records are not controlled by it’s own Character Logic.

Obviously we don’t have the Player table in the Backend Database. Unless we were going to have a few Pre-Created Player records, which we’re not.

Character

| Character | |

| ID | |

| ObjectID | |

| ClassID | |

| FactionID |

The Character table has the most interaction within the Database after the Object. It’s what you will be dealing with when playing the Game (kind of).

A Character could be the Innkeeper. It could be You, or your mate “KillrAwesome”. It could be the Dragon at the end of the Golden Bricked Road.

All the technical aspects that the Engine needs to know about are found in the Character’s Object record.

What the Character has is Context. Character records can have Item records attached to them, via the Equipped table. They can have Stats, like Strength, Courage, Snoozing Skill, via the Statistic table. And Character records have DialogHistory, which tracks their Conversations. I deliberately didn’t link the DialogHistory to the Object table.

That is, we only record the History of the Character. Sure, any Object can have a Conversation with another Object, but I decided against recording all of these. Only the Character records have DialogHistory records. Actually, only Player Characters have DialogHistory records. Let’s not stress the Engine out too much.

The Character has a Class record and a Faction record.

It would be cool to have multiple Classes for a Character, mix and match them, but I haven’t had the time to work that out. From a Design point of view, and to try and understand how the Engine would do it.

Also, multiple Factions would be very cool (ala WoW), but for the moment, a Character can only have one Faction.

Of course, it’s pretty easy to change that. We have a CharacterFaction table to link them, and remove the FactionID in the Character table.

Faction

| Faction | |

| ID | |

| Name |

Faction records are what helps the Engine to figure out Action Context. Is the Character that the mouse is hovering above a Friend or Foe?

Class

| Class | |

| ID | |

| Name |

Well, we pretty much know what this is. This is where you set up the Barbarian Class, with Statistic records like STRENGTH = 25, AGILITY = 20, INTELLGENCE = 40. Right? Who says BarBar’s have to be dumb.

Item

| Item | |

| ID | |

| ObjectID | |

| Type | “Weapon”, “Armor”, “Container” |

| SubType | “Sword”, “Shield”, “Wand”, “Chest” |

The Item table is an obvious inclusion. Phat Loot. Plus, so much more.

It’s worth noting that an Item record can have a bunch of Statistic records attached. This allows you to give a Wand “+5 Fire Damage” in addition to “10 Damage”. It means a Shield could have “+10 Normal Armor”.

Statistic

| Statistic | |

| ID | |

| ParentType | “Item”, “Character”, “Class” |

| ParentID | |

| Type | “Skill”, “Attribute” |

| SubType | “Base”, “Add”, “Subtract” |

| Value |

This one wasn’t so straight-forward for me.

It was easy to figure out the parent attachments. Character. Item. Class.

Where things get difficult is visualising how the Engine is going to parse the Type/SubType/Value information.

Originally I just had Type and Value. But how do you tell the Engine that this Sword gives a +10 to the “Strength Of A Bear” Skill? And how do you give a Character, or a Class, the “Strength Of A Bear” Skill itself?

So the SubType field was introduced. I think it works. But you can probably make it better.

Animal, Building, Vehicle

| <Name> | |

| ID | |

| ObjectID |

Decided to lump the three of them together. Each of them are linked to the Object table. It’s just up the Engine to know what to do with them.

That is, what Pathing AI does this Sheep (Animal) have? What about this Cart, what will happen when it hits the Sheep (the Sheep will win, because Sheep have Wool, and Wool in this world is made of Adamantium, thus Sheep are Wolverine clones and conquer all). Ahem.

The Animal table is linked to the Equipped table. I suppose that, if the Engine allows you to destruct (or kill) Vehicles and Buildings that you could attach it to them also.

But specifically I was thinking about when a Player might shoot a Deer and want to skin it.

Equipped

| Equipped | |

| ID | |

| ParentType | “Character”, “Animal”, .. |

| ParentID | |

| Type | “Finger”, “Head”, “Eye”, “Belt”, .. |

This is where we put Item records on Characters (and other tables).

I imagine the Equipped table would be mostly filled in-game. So the Engine would create stuff for those Orcs over there at some stage, based on some game rules. Or you could hand-plant it all. Shudder.

However, especially for Player Character records, you would need to store these records. Also, for Characters with unique items.

DialogRoot

| Equipped | |

| ID | |

| ParentType | “Object”, “Area” |

| ParentID | |

| Type | “Quest”, “Conversation”, .. |

Okay, heading down the straight.

Dialog is a big deal. It’s far harder than I imagined, although some folk have obviously got it worked out.

Dialog is what an Object will Communicate. A Conversation is what two Objects have between each other, exchanging Dialog.

With that in mind, we have these structures. DialogRoot, DialogItem, DialogItemReq and DialogHistory.

The Type field of the DialogRoot table basically says to the Engine “This is a Quest Dialog”. The Engine then knows what to do in that context. At the moment I’ve only come up with the two Types (“Quest” and “Conversation), but there are no doubt more.

Instead of giving an ObjectID in the DialogRoot table, we have the Parent fields.

You want to be able to assign specific Dialog to a Quest-Giver, for example, but you also want the BarKeep to pull out some Dialog from a general Pool. So we have “Object” or “Area” as the parent, Area obviously being for the general pool.

DialogItem

| DialogItem | |

| ID | |

| DialogRootID | |

| ParentItemID | For the chaining together of Dialog Items. |

| Primary | So that you can have one Item in the Chain as a Primary. |

| ObjectID | |

| Action | “Shop”, “Request One”, “Request All”, “Give One”, “Give All” |

This is what the Player will interact with a fair bit.

“Hi there Xena! Would you like to see the hundreds of Weapons I somehow store about my person?”

That’s a DialogItem. It’s DialogRoot parent would be of Type=”Conversation”.

The ParentItemID field is so that a single Object can have more than a single Dialog Conversation with you.

This is especially important in Quest Dialogs. Most Quests will have at least two DialogItems records. After all, the Quest has be given and then completed.

An instance where this isn’t the case is where one Object gives the Quest and a different Object accepts the completion of the Quest.

The Primary field is a nifty little BYTE that tells the Engine to return to this DialogItem when, for example, the Player returns to the Innkeeper. It might not neccessarily be the first DialogItem record in order. You might want to have the initial Conversation start with “My you are one ugly warrior”, but then whenever the Player initiates Conversation with them, the Innkeeper would use a different DialogItem record. Something like “We serve Beer and Roast Beef. Also, we have Beer.” would be more appropriate.

The ObjectID field allows the Engine to put together Quests that span a bunch of Objects. Like a Scroll which initiates a Quest that has to talk to Mrs. MyHusbandIsMissing, then head out and find the Husband, talk to him, bring him back and then talk to Mrs. MyHusbandIsMissing to complete the Quest.

Finally, the “Action” field allows the Engine to know this is a Question, and if the Object having the Conversation gives Success (a “Yes” usually), then the Action is started.

For example, Xena walks up the Weapon Merchant, who asks the question above. It is of Action=”Shop”, so the Engine knows a) This is a question, so stick up “Yes” and “No”, and b) if “Yes” then open up the Shop interface.

DialogItemReq

| DialogItemReq | |

| ID | |

| DialogRootID | |

| DialogItemID | |

| ObjectID |

This table is how the Quests fit together.

If you have a Quest where the Player must find “The Staff Of Roast Chicken Cooking” and return it, the following would need to be entered:

- The DialogItem record for the completion of the Quest would need an Action “Request”.

- There would be only one DialogItemReq record. It would point to the Object record for the above Item.

- Further, you would need a child DialogItem record for the giving of the Quest Rewards. This would be of Action=”Give One” or =”Give All”, and have any number of DialogItemReq child records.

- If the Action=”Give One”, then the Engine asks the Player which of the linked Objects (through the DialogItemReq) they would like.

- If the Action=”Give All”, then the Player gets them all.

We link to an Object, because sometimes a Quest might want more than an Item. It might want an Animal. It could want another Character.

And more, the Quest reward might be the choice between two Characters, or it might be to give you a Black, Red and Golden Dragon.

DialogHistory

| DialogHistory | |

| ID | |

| DialogRootID | |

| DialogItemID | |

| CharacterID |

This table tracks all the Conversations that a Character has. As mentioned above, for our purpose in this Series, we only care about the Player.

The DialogHistory table is a record of where the Player is in the Game. How far along the Main Quest are they? Did they solve that riddle about the Ten Sphinxes and a Muskrat? How many Trees of Ironwood have they chopped down?

CONCLUSION:

Phew!

If you managed to get through it all, you’ll see I barely scratched the surface of an RPG Database. Really, we only skimmed.

What is important is that we now have a simple framework with which to progress to the most important part of this Series. Clarion!

Until the next post (number three if my internal incrementor is working), Fare Thee Well, and May Your Mead Be Always Frothy!

The pain was excruitiating. It went on for what seemed like an eternity. My body was contorted in a manner that should never befit a prop.

The pain was excruitiating. It went on for what seemed like an eternity. My body was contorted in a manner that should never befit a prop.  It was like a bad scrum where you start yelling "Mayday!". For anyone who”s never been part of the Rugby Union Front Row, "Mayday" is what you yell when things are going bad. Broken spine bad. Face in the mud bad. Obviously, when your face is in the mud you hope someone else is yelling it.

It was like a bad scrum where you start yelling "Mayday!". For anyone who”s never been part of the Rugby Union Front Row, "Mayday" is what you yell when things are going bad. Broken spine bad. Face in the mud bad. Obviously, when your face is in the mud you hope someone else is yelling it.